George Furner Langley

A Port Melbourne man’s role in the North Africa Campaign of World War I

Margaret Bride

The political world map of 1913 is unrecognisable to us in 2025. The fading dominance of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa played a significant part in the events of World War I but most Australians are only aware of Gallipoli and France as World War I war zones. This is in spite of the fact that Turkey, the enemy the allies attacked at Gallipoli, was the centre of it. Nor do we recognise the Ottoman Empire in common parlance as one of our enemies in that war. However, Australian troops fought in north Africa against the Ottoman forces right up to October 1918.

After the failure of the Gallipoli campaign, many Australian and New Zealand troops were sent to France. A lesser number were sent to North Africa to join with British forces in protecting the Suez Canal and allied interests in Egypt, Palestine and the Levant. Among them was Captain George Furner Langley.

George Langley was born in Bay Street, Port Melbourne in 1891 to Jabez Langley, a grocer and his wife, Fanny Martha Furner. He was educated at Nott Street Primary School and then at the Melbourne Continuation School, the first government secondary school in Victoria, later to be divided into Melbourne and MacRobertson High Schools. His first job was as a pupil teacher at Graham Street Primary School, the other Port Melbourne school. His success as a pupil teacher led to his selection into the newly established Melbourne Teachers’ College in Grattan Street, Carlton.

The Langley family were active Christians and members of the large Graham Street Methodist Church, where George became committed to the Christian faith and learned the value of a compassionate and caring community. It also fostered his love of music, particularly singing. From 1911 to 1914 he was an active member of the Army Cadets before enlisting in the first AIF. By that time he had left Port Melbourne to accept a teaching position in Mansfield.

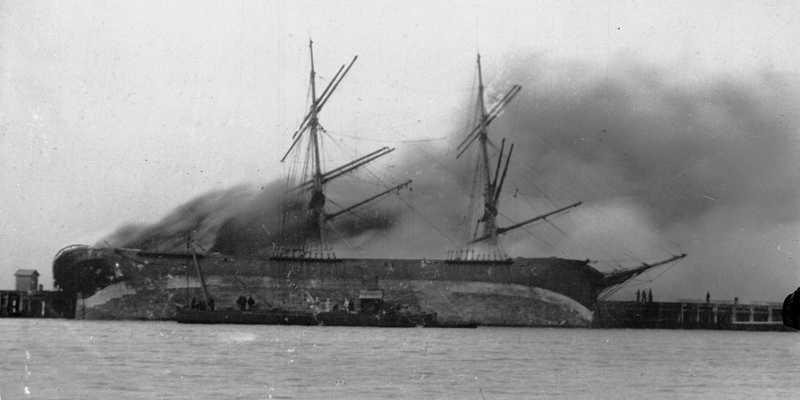

George did well at a variety of sports. He was captain of the Melbourne Teachers’ College Football Team and of their athletics team, competing very successfully in long distance running. These experiences developed his natural leadership qualities so that, in 1914 when he enlisted in the army, he was selected for officer training in Australia rather than immediate transportation to the European war zone. On 3rd November 1914 he embarked at Port Melbourne on the troop ship HMAS Ulysses, transferring later to HMAS Ascanius and landed in Alexandria to begin desert training before taking part in the Gallipoli fighting.

While still on board the Southland preparing to disembark, the ship was hit by an enemy torpedo. “Several men were killed, and an officer of the 21st (Captain Langley) who was sitting on the forward hatch was thrown in the air and fell through the hatch into the bilge … He continued to direct his men both on deck and in their life-boat, until they were picked up, when he collapsed”. 1

He survived his time on the peninsula and was part of the final evacuation in December 1915. He had a short recuperation on Lemnos.

Formation of the Imperial Camel Corps

Although the fighting in northern Europe was the first military priority, there was an urgent need for the British allies to boost their armed forces in northern Africa to prevent the Turkish forces closing the Suez Canal. There were also Egyptians, many of them in the wealthy and powerful class, who were anti-British and pro German. They had observed the loss of British prestige in the defeat at Gallipoli. It was, therefore, essential to neutralise the Turkish threats to Egyptian territory. Turkish agents were inciting Senussi tribesmen of the western desert to make raids into Egyptian territory in an area where army use of horses was almost impossible. In these early days of motor transport, army logistics needed to use horse transportation as well as mounted soldiers in fighting.

It was planned to have a force move west from the Suez Canal across to the Sanai desert. The obvious solution to the logistical problem was to use camels for transportation of supplies and soldiers. From the existing but poorly organised camel units, an entirely new force of about 4,000 to 5,000 men would become the Imperial Camel Corps under the command of Colonel C.L. Smith. He had experience in the army’s use of camels from his service in Somaliland where he had been awarded a Victoria Cross. Colonel Smith remained as commander of the Imperial Camel Corps until it was disbanded in June 1918.

Initially it consisted of four battalions. The members were mostly from the British, Australian and New Zealand forces. The Australians all volunteered to join. Initially four battalion commanders were selected. One of them was Captain George Langley. Before it went into operations, an additional battery, a field hospital and a signals troop were added.

Australian War Memorial: 1055 25

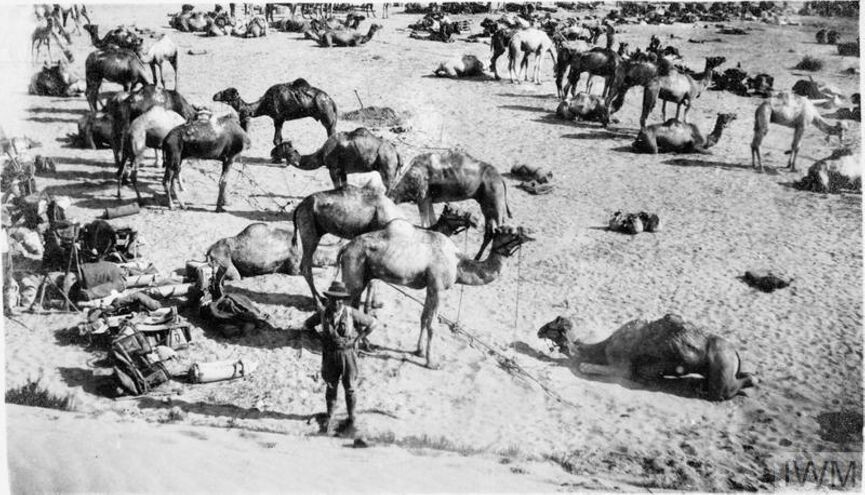

In January 1916, the men and camels entered the training camp at Abbassia for an intense four week training. Very few of the men had any previous experience of camels and some of the camels had never been broken in – a very steep learning curve for all. Camels have a poor reputation. George Langley describes several incidents with his usual humour, incidents that might have had fatal consequences. He describes the camel’s common form of attack if aroused if he is in season:

“… He foams at the mouth, stretches his neck and bares his teeth. When a camel attacks a man he uses his teeth first and then attempts to crush the life out of his victim by kneeling on him and pounding him with his knees.”

The first thing was for the men to learn to get on the camel, no easy task: “each man would take hold of his kneeling camel and turn the head towards him, place one foot on his neck and lift himself into the saddle.” At least that was the theory. At first more than half the men were thrown off balance and the camel stood up unencumbered by any rider.

First Enemy Engagements

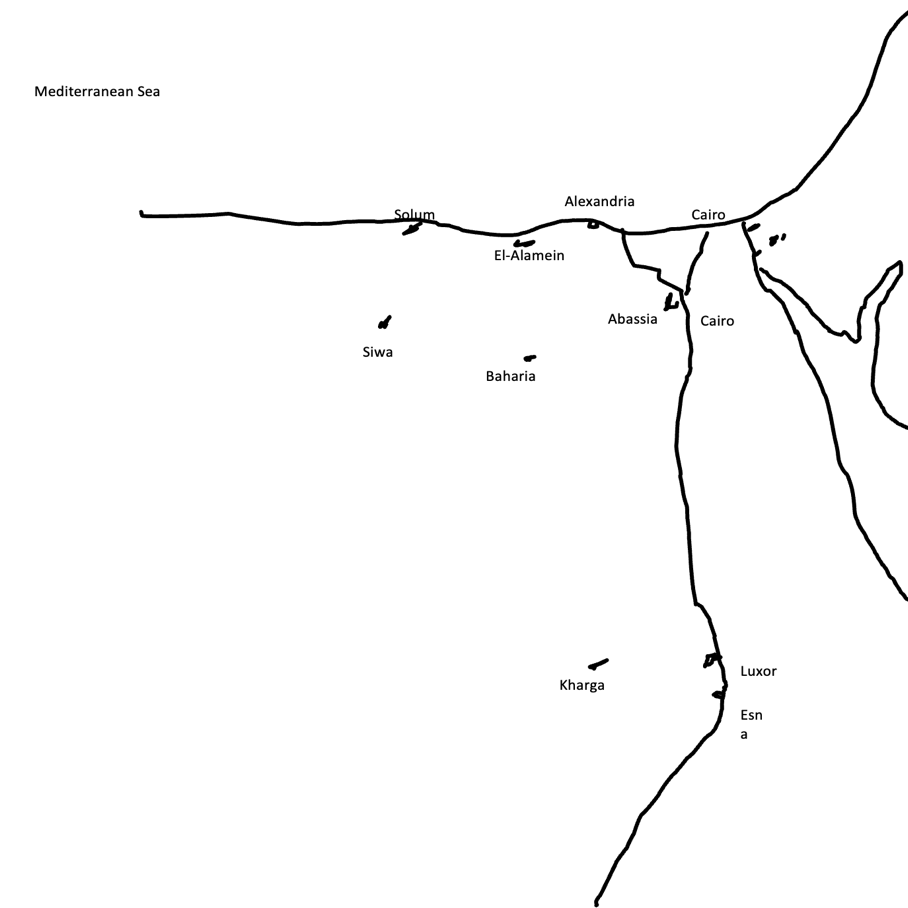

There was a report that there were two thousand hostile Senussi men camped at the Baharia Oasis south-west of Cairo. A patrol of the Camel Corps, along with a small number of armoured cars, was despatched to find them. The conditions were very bad – searingly hot during the day with fierce dust storms blowing up without warning. The force attacked the defences and entered the small town with some casualties but the majority of the Senussi had moved further west toward Siwa.

The first battalions were ordered to move on over difficult country. The sand dunes were sometimes as much as seven miles across and twenty to fifty feet high. The camels had to be led. Sometimes the loads had to be taken off the pack camels and hauled up by the men. These first companies of the Camel Corps then began the work for which they had been formed, patrolling the western desert and rounding up prisoners who were taken on foot to Kharga island just west of Luxor.

George Langley and his battalion were the last to leave the training camp at Abassia, south-east of Alexandria. They were hampered by a shortage of equipment, even saddles. They were ordered to go by train to Esna, forty miles south of Luxor, from where they marched westward across a waterless plain.

In his account of this Langley wrote “Guides were obtained from the district and everything was in readiness for the march. Instructions arrived by cipher wire daily and on the very day the march was due to start instructions were received cancelling all previous orders and instead to entrain at Luxor for Alexandria and then go west along the coast to Alamein”.

This was only one example of the poor leadership of the army command in the war in North Africa: its indecisiveness and lack of basic organisational skills.

The desert patrols were gruelling. About one rest place Langley wrote: “The soft sand was easily dug and each one had his own little box-like funk hole, with a bivouac sheet stretched over the top as a protection against the sun. A few sandbags reinforced the parapet, and on one side of the hole was left a trench to form a couch on which was spread the bed. There were also many disadvantages, the sides had an uncomfortable habit of falling in, and there were the original inhabitants – field mice, ants, small scorpions and beetles and the everlasting fly – harmless but never the less pests”.

Temperatures were extraordinary. On at least one day it was 130º Fahrenheit (540 C) in the shade of an erected blanket. Finding water could be a challenge. On arrival at one oasis the water was so bad that even the camels refused to drink it. They trudged another two hours to a place where their local guides said there was water. There the engineers dug down several feet until enough water seeped into the depression to eventually satisfy the hundred camels and the members of the corps as well.

On arrival in El-Alamein, Langley’s troops began patrols south west of the city to intercept the Senussi north of the oasis town of Siwa. A raid on Moghara was contemplated, but only the advance positions were attacked before a communication came to withdraw. Langley was promoted to Major on 11th September.

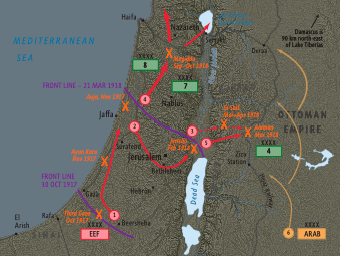

Palestine campaign

(accessed 26.9.2024: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/palestine-campaign-1917-18-map

The fighting now intensified to the east of the Nile river and the approach of a German led force toward the city of Romani. An attack was made by a force of 3,600 men under German command on a mixed Sanai force made up of Australian Light Horse, City of London Yeomanry (at that time a mounted force) and four companies of Imperial Camel Corps. Originally it was intended to use infantry as well but in the horrific conditions of heat and lack of water, in one day 800 men fell out of the ranks, unable to continue. The next day Camel Corps men had to be sent out to rescue them.

The battle for control of Romani was crucial to the defence of the Suez Canal. The contribution of the Imperial Camal Corps and of the Egyptian Camel Transport Corps was important to the allied victory. After the battle for Romani, the allies regrouped before attacking the German led forces that controlled the eastern Mediterranean.

Mid December 1916, camped out in the Sanai, they were all looking forward to the special food of the Christmas celebrations but there was one problem: no fuel. The cooks were struggling to have any fires at all. No problem. Australian soldiers had a great reputation for foraging. Suddenly wood became available. Under cover of night foraging parties went out and cut down the poles that supported the telegraph lines. Army command were outraged and ordered Langley to put a stop to it.

“As the commanding officer of the 1st Battalion of the Imperial Camel Corps, I gave a dissertation on the enormity of the offence and threatened punishment of anyone found in possession of wood, even resembling the telegraph poles. This speech was more than impressive as it was delivered from a high mound which acted as a kind of dais. I was later told the unkind truth that the mound I was haranguing from was composed of a store of cut up telegraph poles buried by my battalion cook.”

In June 1917 morale was low after several apparent tactical blunders by General Murray who was directing the campaign from Cairo. When he was replaced by General Allenby and the headquarters moved to just behind the front line, morale improved. In November Allenby successfully directed the campaign to take control of Gaza, then Jerusalem, Damascus and Aleppo, thus ending Ottoman rule in the region of Palestine.

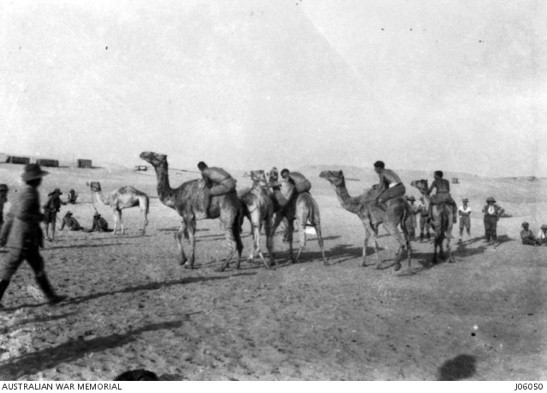

In order to lift morale a sports day was organised at Rafa in September 1917: “There were trotting races, galloping races, wrestling on a camel’s back, musical chairs, tug of war, stunt riding which included trotting and galloping with the rider standing behind the camel’s hump and even a prize for the best turned out camel. Here let me mention my own camel Horace, he was a champion. He mopped up the opposition down on the Canal … the field got away to a good start, and old Horace at once showed prominently. He galloped like a champion and never looked like being beaten. … I still have the pennant .. and look back with quite a degree of affection on that ugly beast Horace.”

In November 1917 the Camel Corps was part of a mixed force of infantry and the Light Horse confined by an enemy attack, unable to defend their position because they did not have any artillery. They had been travelling six weeks without a break, often going days without ever removing their saddles. Finally when they were ordered to move on a quite different challenge confronted them: it rained so heavily that they were almost immobilised by the mud.

“The camels were slipping and sliding all over the place and damaged limbs were becoming quite common place…camels broke down and had to be destroyed. Eventually they reached Shellal. It was at this time that the General’s batman a typical young lad from Glasgow made himself famous. While the troops were held up by the rain he visited a neighbouring village and made many purchases with paper labels from Ideal Milk tins, which some bright local accepted as 5 Bank of England notes.”

The Camel Corps Disbanded

As the allies advanced north into Palestine the country became more fertile. Water was more plentiful. The camels became redundant and the decision was made to disband the Corps. Its members were re-formed into two new Brigades of the Australian Light Horse.

True to the tradition of putting a humorous slant on a serious event a mock funeral was held.

“The corpse was a camel saddle, covered by a flag and carried on a stretcher to the ‘chapel’ (my tent) where it was lowered into its grave. The service was conducted by Padre Houston. The two newly-formed Australian Light Horse Regiments shouldered upturned rifles and added the necessary pomp and circumstance to the proceedings. A volley was fired and the Imperial Camel Corps was buried.”

Many years later, when George Langley was preparing to publish Sand, Sweat and Camels he asked other members of the corps to contribute. Captain Bichan wrote:

“Camels on the march remind me of an elderly gentleman in dressing gown and slippers shuffling down the corridor to the bathroom.”

And Major H.C. Maydor wrote:

“My own impressions, after a year in France were that here were men who knew their way about and did not need spoon feeding. Where in France, each unit … was merely a pawn in the game. … In the desert it was a different story. So that my first impression was that the Camel Brigade had learnt how to adapt themselves, to look after themselves, anywhere and under any conditions.”

Front Row: McLaren, Brigadier G.F.Langley, Brigadier L.Smith V.C., Major J.Mills, *. Millar

Conclusion

George Langley fought in other key advances in the eastern desert and finally in the advance on Damascus in 1918, organised by the Australian: Henry George Chauvel commander of the Desert Mounted Corps. This marked the end of the Ottoman Empire. It was closely followed by the general armistice that marked the end of World War I. He was mentioned in dispatches three times for outstanding leadership.

The role of the Camel corps was vital in carrying water to the fighting troops, in one instance arriving only hours before the men, who were in the last stages of dehydration, would have died in large numbers. Water and wood were essential to the fitness of the troops. Langley retells the unconfirmed story that Australians from the Camel Corps tried to remove the walls of General Broadbent’s hut while he was working at his desk. On another occasion a despatch was sent to warn the sentries at a wood dump to watch out the Camel Corps were coming, a warning that came too late as they had already raided it for wood to cook. In today’s terminology the men of the Corps were enterprising.

Before he returned to Australia, George married Edmee Plunkett, daughter of a British Army officer who had lived in Cairo for much of her life. Edmee was a graduate of the University of London, a woman fluent in Italian, French, Arabic and English: Edmee had, what were considered for her time, advanced views on the role of women in society. When George met her she was working in Cairo as the confidential secretary to Lord Edward Cecil, British Financial Adviser, a post previously held by a male.

George was a strong believer in the state education system and had a distinguished career in the Victorian Education Department as a school principal eventually serving as principal of his old school, Melbourne Boy’s High School 1949 to 1956.

References

1 C.E.W. Bean vol II The Story of Anzac. Official history of Australia in the War of 1914-1918.

Quoted in The C.E.W. Bean vol 11 The Story of Anzac Soldier, page 31)

The Sentimental Soldier: a life of George Furner Langley, Alan Gregory, pub. Langley, Curtis, Thompson Library Trust, 2008

Sand, Sweat and Camels, George F. and Edmee M. Langley, Seal Books, 1995

The Australian War Memorial: https://www.awm.gov.au/, accessed on numerous occasions October 2024

Map of Palestine 1916: Accessed 26th September 2024

Australian Dictionary of Biography, George Furner Langley, A.W. Hammett

Australian Dictionary of Biography, Sir Henry (Harry) Chauvel, A.J. Hill. Accessed on line 2nd October 2024