The Flu Epidemic of 1919

by Claire Johnson

In May 1918, reports of a mysterious and deadly disease ravaging Europe began to reach Australia, causing concern amongst those who had family members involved in the war in Europe. By July, England was affected, and Australian newspapers and letters from soldiers kept the Australian public informed.

Dubbed the ‘Spanish Flu’, it was a variant of swine flu, highly contagious and killing up to 20% of those who caught it, with the most vulnerable being adolescents and adults in the prime of life. It was characterised by a sudden onset and rapid deterioration, affecting the populace in three waves with a lull of several weeks between each wave. Initially it was thought that each lull was the end of the epidemic, but by the time it reached our shores the pattern had been identified.

From October 1918 to the end of April 1919 Australia enforced quarantine (varying from 4 to 7 days) on all ships coming in, whether there was sickness aboard or not. As the main port of entry to Victoria, the Port of Melbourne was in the front line.

Returning troopships were a major concern, being so crowded that the risk of cross-infection was extremely high. They needed to refuel in South Africa, where the disease was rampant and the death toll appalling.

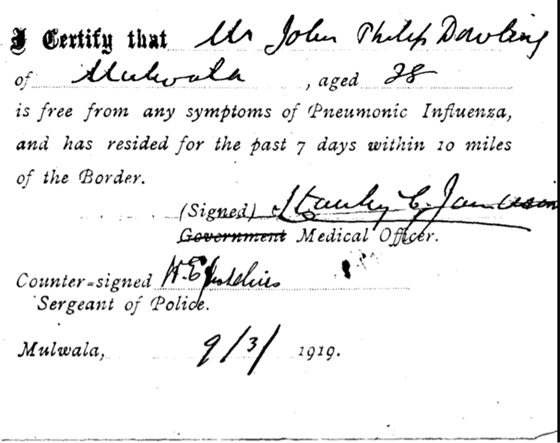

At a meeting in November 1918, Commonwealth and State leaders determined that if any State had a case of pneumonic influenza, the Commonwealth was to be informed immediately and would proclaim that State infected. The State borders would be closed, and permits required to travel from an infected State into an uninfected State. Goods and mail could continue with extra care taken.

State and local authorities were required to find suitable facilities for influenza patients and to staff them, the latter made more difficult by the numbers serving overseas. Serum was made available for free inoculations.

When a case was identified, both the doctor and the householder were obliged to notify the local authorities. The patient could be nursed at home or taken to a fever hospital; those in contact would go into isolation. In Victoria, a breach of any of the regulations could incur a fine of up to £20 plus £1 to £5 per day.

When a case was identified, both the doctor and the householder were obliged to notify the local authorities. The patient could be nursed at home or taken to a fever hospital; those in contact would go into isolation. In Victoria, a breach of any of the regulations could incur a fine of up to £20 plus £1 to £5 per day.

The conference also recommended that in the event of an outbreak it would be advisable to close all places of public resort.

The first cases in Australia were identified in January 1919.

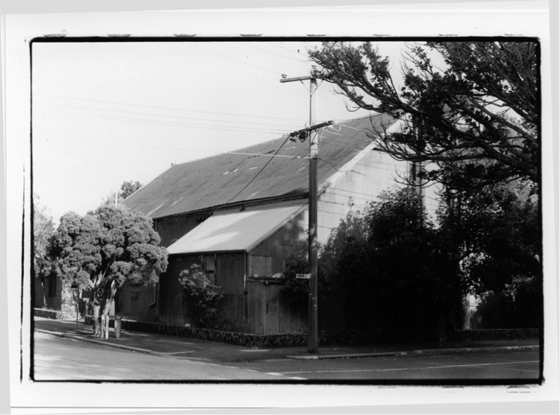

Inhalatoriums were set up by Councils and by some businesses, and large department stores had them inside their main entrances. In Port Melbourne, an inhalatorium was established at the Excelsior Hall, and on 15th February, 1919 the Port Melbourne Standard reported that 821 people had visited the facility in the previous two weeks. All that was needed was a small room with a convenient supply of steam from a nearby boiler. Sulphate of zinc, a disinfectant, was added to steam before a jet of it was sprayed into the room.

The Chief Medical Officer Dr Davis reported 200 people per day were being inoculated at the Port Melbourne Town Hall, and he had carried out further inoculations at Swallows & Ariell and other large employers in the area.

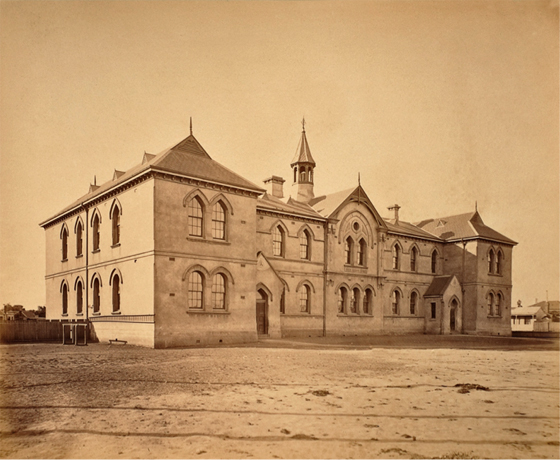

While the Exhibition Building became Melbourne’s primary fever hospital, the Nott Street State School remained closed after the summer holidays and was requisitioned to be the local facility. Five wards, a doctor’s surgery and an office were fitted out. Nurses and volunteer staff had to remain on site and were provided with a dormitory, a dining room, a bathroom and a laundry. The kitchen was proudly described as state-of-the-art with large gas stoves. Mrs Davis (wife of the Council’s CMO) did all the cooking. The infants’ school was set up to accommodate the children of those who were in hospital and volunteers were sought to mind them.

An ambulance of sorts using a covered-in wagon was pulled by horses supplied and driven by Mr H or Mr Bert Jennings. George Beazley and Bob Jones volunteered to be stretcher bearers.

On 15 Feb 1919, there were sixteen patients with five nurses including Nurse Whiter, and three voluntary staff consisting of another local woman, Mrs Evans, and two girls from Richmond who had volunteered through the YWCA.

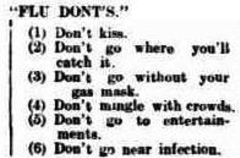

Masks became compulsory in New South Wales and the Port Melbourne Council advised people to wear them. Dr Davis said he wore a mask made of eight layers of gauze, a pattern for which was left in the Town Hall at Council’s request. Newspapers and magazines printed patterns and instructions for making masks.

In February the Anglican, Presbyterian and Methodist Sunday Schools closed, the Graham Street church held services outdoors and the parishioners of Holy Trinity were asked to wear masks. The Port Melbourne Public Library and the Mission Hall in Bay Street closed. The library reopened two months later, refurbished and enlarged to twice its size. Port Melbourne Standard called for people to door-knock, and for donations of food and linen. The Town Clerk, A V Heath, requested donations of clothing and boots.

In his report to Council on 8th April, Dr Davis stated that there had been 132 cases in two weeks compared with only 28 cases in the previous two weeks, demonstrating the typical lull between waves of outbreaks. Unfortunately the Nott Street hospital had closed due to a shortage of nurses. Dr Davis added,

“There is a family residing at 61 Esplanade West in a condition of great hardship. This household consists of a man, his wife and five little children. The man and his wife were very unwell on Saturday. I could only get the man and his wife admitted to a hospital by menacing the central public health authorities in Melbourne with the most dire threats. The five little children are still in the house. They are being cared for by a neighbour, a woman, who is doing her best for them. All the five children were sick. Now two of them are dangerously ill. The circumstances are tragic.”

This sad account referred to Lawrence McGlade and his family. Lawrence aged 36 and Ethel (nee Burke) aged 33 died in Prahran. They had consecutive death registration numbers.

In early May, 200 people responded to a call for volunteers to form a local Red Cross to assist Dr Davis in combatting influenza. By 20th May the second wave was over but Dr Davis warned that the third wave was yet to come. He suggested that a tent hospital be set up at Albert Park but the Albert Park drill hall was preferred. In July, the Council’s influenza relief kitchen was reopened during the final wave of the disease which was all over by September.

Here are just a few of those who lost their lives to the deadly epidemic:

Mr Andy Menzies of Stokes Street lost his wife, married daughter and a son to the disease.

In April, Councillor Morris’s daughter Louise succumbed, despite the best care possible.

Elsie Munro was just 24 years of age when she died. She had married on Christmas Eve, 1914. As her husband Private George Munro was disembarking at the pier after four years at the war, Elsie was being transported by ambulance to the Homeopathic Hospital where she died the following day. She had been ill for six days.

Twenty-three-year-old Isabel Fraser from Bendigo who was living with her sister, Mrs V Eddy in Pickles Street, went to the theatre in the city with her friends on Saturday night, fell ill on Sunday and died on Tuesday.

It is unknown exactly how many Port Melbourne residents died in the epidemic. Some earlier deaths were simply attributed to pneumonia as doctors were unsure of the diagnosis. No State wished to go into quarantine, and there were accusations levelled against Victoria for late disclosure.

1 Comments

Tom Frey

Thanks Claire for a valuable piece of Port Melbourne hístory, though a sad one. That sounds a lot like the pandemic we are currently going through. Wish you and all Port Melbournians well in this trying time.

Regards,

Tom