‘Lagoon Reserve’: Residential or Recreational?

by David Radcliffe

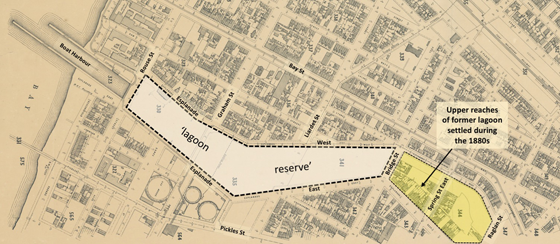

In the 1890s, the name ‘lagoon reserve’ applied to any part of the strip of reclaimed land, bounded by Esplanade East and Esplanade West, extending from Bridge St to Rouse St. Formed by filling in the Sandridge Lagoon, it was also known as the ‘lagoon lands’. The recreational park we know today as Lagoon Reserve, between Liardet St and Graham St, is only the middle part of the original ‘reserve’. William Thwaites, the engineer who proposed the reclamation scheme, built the business case for the project on the assumption that all the reclaimed land would be sold for housing or commercial activities to offset some of the costs of doing the work.1 However, nothing is ever that simple.

Once a pristine hunting ground, the lagoon had deteriorated to become a noxious, smelly, heavily polluted dumping ground for all manner of waste. The shallow upper reaches, from Bridge St to Raglan St, had been gradually filled-in from the 1870s with much this new Crown Land being auctioned off in 1883/84. By the mid-1890s many workers cottages had been erected there.2 The fate of the remainder of the lagoon was settled in 1889 with the passing of the Port Melbourne Lagoon Act. The Act resolved once and for all the ‘Lagoon Question’, a contentious issue that had dominated civic life for decades. Its provisions were the outcome of political back and forth involving the various parties over the preceding three years.3 The reclamation process included the installation of a drainage system to capture runoff that had hitherto flowed into the lagoon and pump it into the Hobson’s Bay.

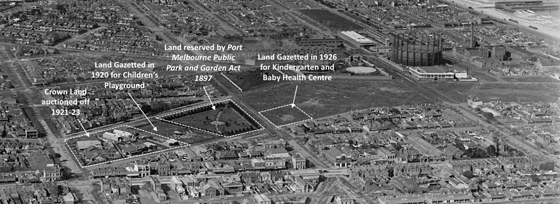

Locals soon took advantage of the reclaimed land for recreation. In September 1893, employees of the Marshall & Co boot factory sought permission to use the land between Bridge St and Liardet St to practice cricket.4 Noting that it was Crown land, the Council nevertheless saw no problem with it being used for this purpose. Subsequently scheduled cricket fixtures were played on this northern section of ‘lagoon reserve’. 5 It became the home of the North Ports Cricket Club6 and as late as 1920 returned soldiers played there, across from Chequers Inn (now the Bay & Bridge).7 However, recreation eventually gave way to some residential development.

The best use of the ‘lagoon land’ was a source of political debate, government lobbying and ongoing frustration up until the 1930s. The Port Melbourne Public Park and Garden Act of 1897 reserved two acres of the ‘lagoon land’ on the northern side of Liardet St. The mayor at the time was Henry Norval Edwards so the area became known unofficially as “Edwards” park. In 1902, locals were less than impressed with state of the “park” now fenced off.8 In late 1914, enterprising locals began removing much of the fencing.9 Finally, in 1917, a serious attempt began to develop Edwards Park, creating the now familiar, diagonal, crossed pathways.10

Over the years, the Premier and others inspected the ‘lagoon lands’ and there was much back and forth. Some argued that the “Edwards” Park land should be exchanged for the five acres between Liardet St and Graham as a recreation area. The Government wanted to sell some of the land. In the end, 14 allotments at the northern end, adjacent to Bridge St, were auctioned off with many locals in attendance to protest the sale.11 The remaining acre of land between Bridge St and Liardet St was reserved as a children’s playground, which is still there today.

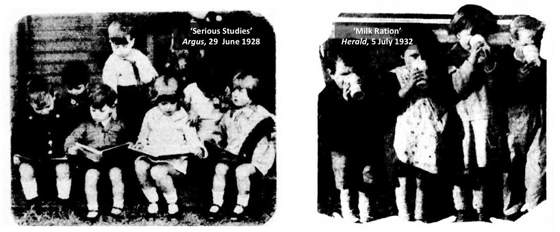

The welfare of children was also advanced when Lady Forster, wife of the then Governor General, visited Port Melbourne to open a new kindergarten in December 1924.12 Part of the Free Kindergarten Union, initially it operated from the Salvation Army Hall in Spring Street East. Funds were raised to construct a purpose-designed facility which opened in June 1928 on the middle section of the ‘lagoon land’ at the corner of Liardet St and Esplanade West.13

The land had been gazetted in 1926 for an “institution of public instruction (kindergarten)”. A baby heath centre was also built on this site, next to the kindergarten.14 Although fashions and food choices have changed, nearly a century later youngsters still gather on this part of the ‘reserve lands’ for play, learning and nourishment.

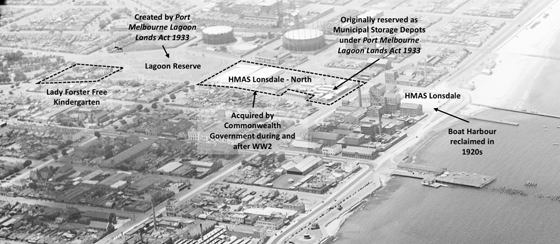

In 1933, the Port Melbourne Lagoon Lands Act resolved many of the unanswered questions about what to do with the other parts of the original ‘lagoon reserve’. The remainder of the land between Liardet St and Graham St was set aside as a permanent reserve, Lagoon Reserve. The Council undertook beautification work15 and a turf wicket was laid.16 Two parcels of land near the Rouse St end were set aside as a municipal depots and Esplanade East, south of Graham St, was narrowed. However, world events caused the use of this southern end of the ‘lagoon lands’ to reprioritised.

In the late 1920’s the last remnant of Sandridge Lagoon, the boat harbour running from Rouse St to Hobson’s Bay, was reclaimed by the Harbour Trust.17 In 1937, Cr Bertie proposed that this become a picnic area for families by the foreshore. However, the outbreak of the Second World War changed everything. In 1942, this land was acquired by the Commonwealth and the naval training base HMAS Lonsdale was erected there. During the war and soon after, all of the land between Rouse St and Graham St (except for the pumping station) was acquired for naval purposes, becoming known as HMAS Lonsdale – North.

After the naval base closed in 1992, the land between Rouse St and Graham St was developed as the Port residential apartments and that south of Rouse St as the HMAS Apartments. One wonders what William Thwaite, engineer to Marvellous Melbourne,18 would make of the many twists and turns in the use of the land his scheme reclaimed in the late nineteenth century.

[1] ‘Mr Thwaites amended plans’, Standard (Port Melbourne), 14 January 1888, p. 3.

[2] David F Radcliffe, Changing Fortunes: The Ebb and Flow of People and Place in a Pocket of Port Melbourne, Penfolk Press, March 2020.

[3] ‘The Lagoon’, Standard (Port Melbourne), 11 December 1886, p. 3.

[4] ‘A new cricket ground’, Standard (Port Melbourne), 23 September 1893, p. 3.

[5] ‘Matches to be played’, Standard (Port Melbourne), 24 September 1898, p. 3.

[6] ‘Visit of the Premier’, Standard (Port Melbourne), 19 February 1910, p. 2.

[7] ‘Soldiers’ Matches’, Port Melbourne Standard, 10 January 1920, p 3.

[8] ‘Items of News’, Standard (Port Melbourne), 23 March 1901, p. 2.

[9] ‘Industrious residents make a haul’, Port Melbourne Standard, 9 January 1915, p. 2.

[10] ‘Edwards Park’, Port Melbourne Standard, 7 April 1917, p. 2.

[11] ‘Port Melbourne “Lagoon” Land’, Record (Emerald Hill), 12 November 1921, p. 4.

[12] ‘Vice-regal visit’, Record (Emerald Hill), 20 December 1924, p. 5.

[13] ‘Lady Forster Kindergarten’, Age (Melbourne), 29 June 1928, p. 11.

[14] ‘Baby health centre’, Record (Emerald Hill), 27 August 1927, p. 7.

[15] ‘Improving the lagoon land’, Record (Emerald Hill), 28 March 1936, p. 6.

[16] ‘Lagoon proves popular with cricketers’, Record (Emerald Hill), 19 November 1938, page 3

[17] ‘Picnic ground near beach’, Record (Emerald Hill), 20 November 1937, p. 1.

[18] Robert D La Nauze, Engineer to Marvellous: The Life and Times of William Thwaites, Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2011.