William and Christiana Barlow

by David F Radcliffe

In November 1862, William James Barlow, aged 29, married Christiana Caroline Stivey, aged 18, at Holy Trinity Church in Bay Street. They started married life in a rented four-room wooden house at the very southern end of Station Place. Christiana gave birth to their first child, James, in early 1863. Later that year, the young family were impacted by a flood resulting from a massive gale and high tide.[1] Fortunately, Barlow was one of twelve employees of the Victoria Sugar Company who shared £50 to help them recover.[2] Christiana and William had ten more children, one every couple of years with the last arriving in 1885. With their growing family, the Barlows moved home often, enabled by William’s real estate and business success.

Born in Chelsea, London, William Barlow arrived in Sydney as a baby in 1833. His father, a blacksmith, set up a business there but passed away just three years after coming to Australia. His mother remarried. In mid-1859, William’s older brother Richard, a refiner at the Colonial Sugar Refinery (CSR), moved from Sydney to Melbourne to help set up the Victoria Sugar Refinery works on the Sandridge foreshore. William and their younger sister Maria followed. When Maria married Edward Carse, a scripture reader[3], in December 1862, Christiana and Richard were the two witnesses.

Christiana was born in Devon. She arrived in Melbourne in July 1854 as a ten-year-old on the barque Ontario with her father, a carpenter, her younger brother, and their stepmother. They were accompanied by her father’s brother, also a carpenter, and his wife. This was the peak period for people arriving here to seek their fortunes on the Victorian gold fields. The Ontario was the first emigrant ship from Southampton to have a “baking apparatus” on the deck so passengers could have fresh bread rather than relying on that much-detested staple, hard tack.[4]

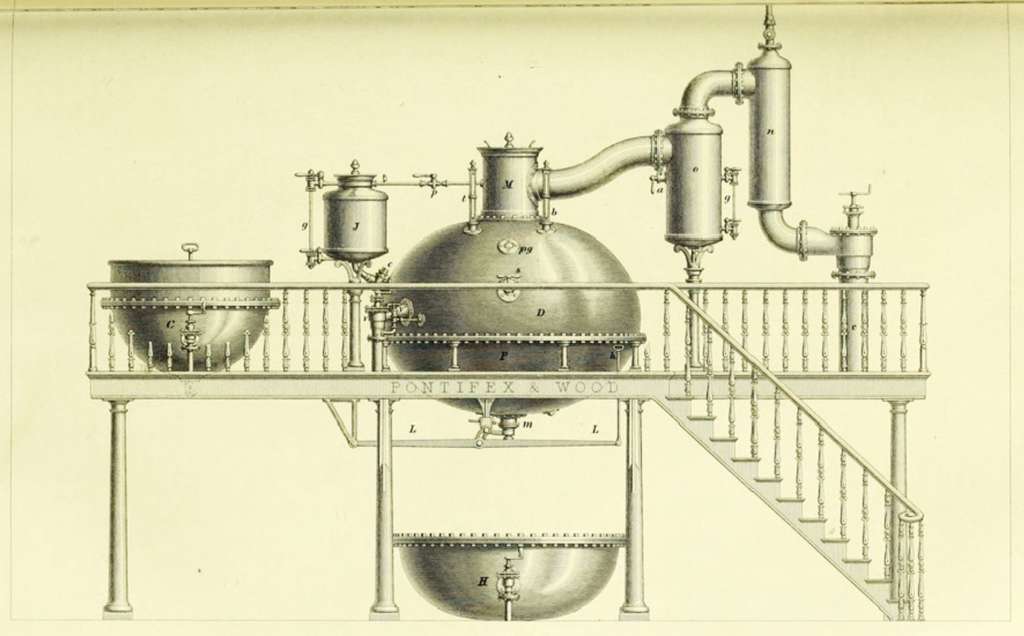

William Barlow’s trade was as a machinist and during the 1860s he worked as a ‘sugar boiler’ at the Sandridge refinery. The vacuum pan used to boil the syrup to produce crystals of refined sugar was the most technical of the processes in the refinery.

Everything changed in June 1875 when the sugar refinery was destroyed in a major fire. A month later the decision was made to move operations to Yarraville rather than rebuild the facility here, putting upwards of 250 people out of work.[5] Richard returned to Sydney to assist Frederick Poolman with building the CSR sugar refinery that opened at Pyrmont in 1878.

William stayed in Sandridge becoming a building contractor, possibly in association with his father-in-law and brother-in-law. Commencing in the mid-1860s, while working at the sugar refinery, he had began to buy and sell property. Having already been quite successful at it, the closing of the refinery opened the way for him to make this his full-time occupation. The street where his real estate ventures began now bears his name.

In 1877, William purchased a substantial double-fronted brick villa at the northern end of Nott Street, past Raglan Street, with land running through to Station Place (now Station Street). The house had a front veranda laid with tessellated tiles, a hall, a drawing room, a dining room, three bedrooms, a detached kitchen, two other bedrooms and out offices fitted with marble and slate mantelpieces, register grates and chandeliers. He also owned several other properties nearby on Nott Street and Station Place. Real estate had been good to William and Christiana.

But there was sadness also, with their eldest daughter, Alice, dying of typhoid fever in 1878, just short of her seventh birthday.

William was now well-established in the community. He was a long-standing member of Holy Trinity Church and was appointed one of its auditors in 1880.[6] When the parishioners of the church had requested in 1868 that the controversial Rev. Frederick Platts resign, both William and Richard Barlow were signatories along with many prominent citizens, including Thomas Swallow, William Morley and Thomas Traver.[7] William contributed £10 towards the Rev. Platts resignation fund.[8] Ironically, it was the Rev. Platt who had officiated at the weddings of William and Christiana, and Maria and Edward Carse.

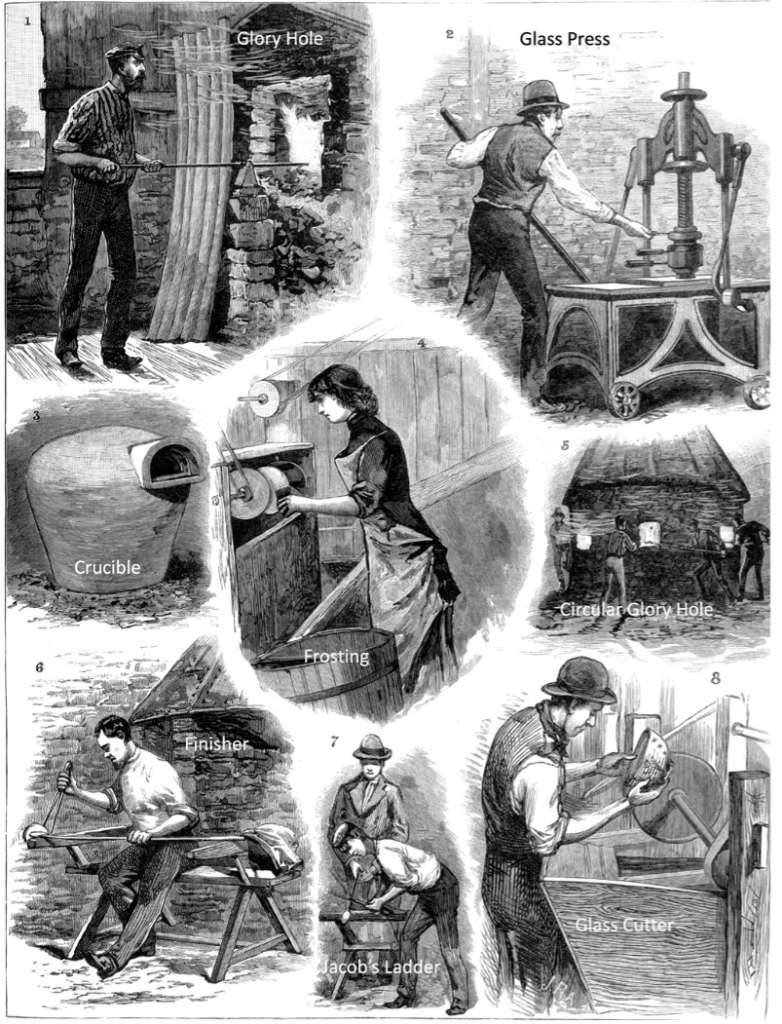

In addition to real estate, William Barlow returned to his industry roots when he co-founded the Australasian Glass Manufacturing Company in 1878 with GH Jamieson.[9] They established a modest factory on land owned by Barlow in Richmond. However, in early 1879 operations moved to Graham Street across from the South Melbourne Gasworks, after Australasian Glass raised additional capital and purchased the Victoria Flint Glassworks, which was located there.[10] The glass workers were artisans.

A fellow director of the Australasian Glass Manufacturing Company was Robert Byrne, a prominent auctioneer and partner in the firm of Byrne, Vale, and Co. Byrne had commenced his political and real estate career in Port Melbourne in the 1850s purchasing substantial amounts of property around the district at Crown Land auctions and then selling it for a profit. From the late 1870s, Barlow’s real estate transactions usually involved either Robert Byrne or William Blair, a lime merchant and well-known resident of Essendon.

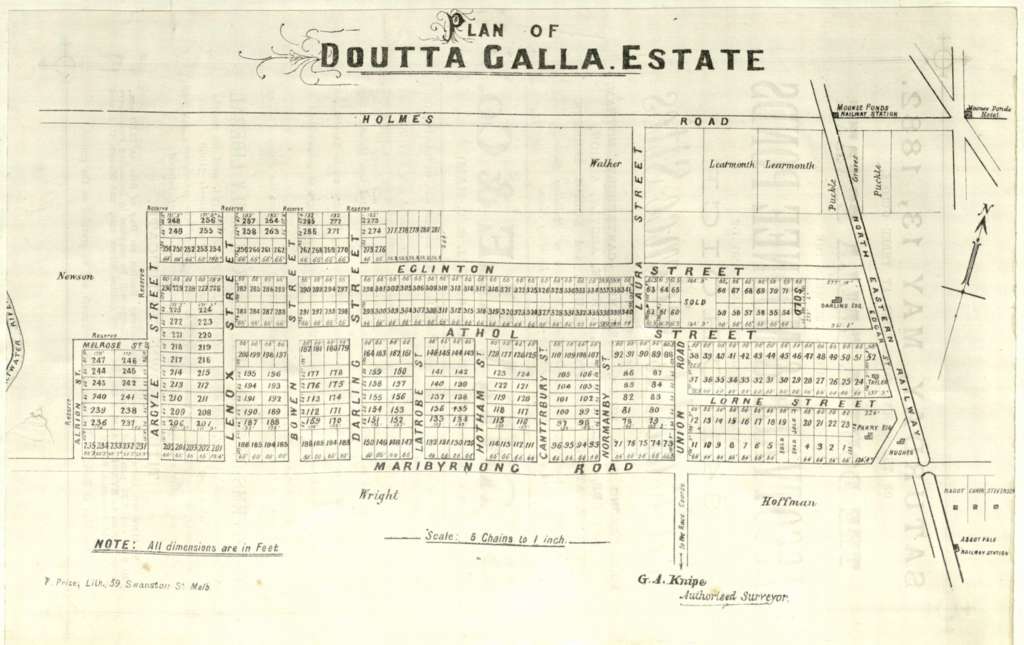

In 1882, Barlow made a couple of large, speculative, and highly leveraged real estate investments. One was the massive Doutta Galla Estate in Moonee Ponds which he bought with a partner in April for £13,600. The other was the Devonshire Estate in Essendon purchased from Blair in November for £6,700. Closer to home, he built and rented a row of six houses on Ross Street, Port Melbourne, known as Barlow’s Cottages in 1883.

But William had over-extended himself and his assets were sequestered in April 1884. His case in the Insolvency Court revealed financial difficulties going back several years, with large debts, multiple mortgages, and poor bookkeeping.[11] His family villa on Nott Street was sold in May. The land boom of the 1880s produced many more insolvents when real estate values plummeted in the 1890s. One of these was Robert Byrne.[12]

William Barlow applied for a discharge certificate in October 1884 so he could trade again. He established WJ Barlow & Sons in City Road, South Melbourne near Moray Street making marble mantelpieces. But William died less than two years later in September 1886, aged just 54, following a stroke, having suffered from chronic kidney disease for five years.

In the short time since he was discharged as a bankrupt, William had acquired real estate valued at £4,700. This included him regaining the brick villa at the top of Nott Street, which is where he passed away. But he also had considerable liabilities including first and second mortgages on rental properties he had in Prahran. A legal dispute between Vale and Blair, related to Barlow’s earlier real estate dealings, was not resolved until 1887.

While the older Barlow sons were now in their late teens and early twenties and relatively independent, Christiana was left to bring up six children ranging in age from one to thirteen.

Their second son, Edward, took over the reins of WJ Barlow & Sons. The firm developed a new process in 1888 to create artistic designs in enamelled wood for mantelpieces and bench tops. This innovation was well received locally and in Sydney.[13] Unfortunately, WJ Barlow & Sons became insolvent a year later due to debtors not settling their accounts.[14]

The only picture we have of the Barlow clan is that of William and Christiana’s eldest son, James, his wife Catherine and their seven children. They settled in Dow Street, Port Melbourne, in 1904 having moved between Kensington, South Melbourne, Albert Park, and Port since their marriage in 1891. James worked as a labourer at the South Melbourne Gasworks, witnessing the dangers of workplaces in that era, and the fatal consequences of a missed step.[15]

Christiana Barlow passed away in 1914 aged 70. She and William had 28 grandchildren, a legacy that transcended the ephemerality of real estate gains and losses.

Acknowledgement

The photograph of James (Jim) and Catherine (Kate) Barlow and their children was donated to the PMHPS by Fay Walker (nee Hampton), daughter of May Inga Barlow, the two-year-old leaning on Kate’s leg in the photograph. Fay, a great-granddaughter of William and Christiana Barlow, passed away in Castlemaine in 2022, aged 93.

[1] 1863 ‘Severe Gale and High Tide.’, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.:1848 – 1957), 15 December, p. 5., viewed 16 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5740978.

[2] 1864 ‘Advertising’, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.: 1848 – 1957), 20 January, p. 3., viewed 20 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5742752.

[3] 1907 ‘In Memoriam.’, The Sunbury News (Vic.:1900 – 1927, 14 December, p. 2., viewed 21 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66845960.

[4] 1854 ‘Shipping Intelligence’, Adelaide Observer (SA:1843 – 1904) 20 May 1854: 7. Web. 15 Jul 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article158097427.

[5] 1875 ‘Sandridge Sugar Works,’, The Record and Emerald Hill and Sandridge Advertiser (Vic.:1872 – 1881), 9 July, p. 2., viewed 16 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108498683.

[6] 1880 ‘Local Patronage.’, The Record and Emerald Hill and Sandridge Advertiser (Vic.: 1872 – 1881), 30 January, p. 2., viewed 16 Jul 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108501964

[7] 1868 ‘Advertising’, The Age (Melbourne, Vic.:1854 – 1954), 16 May, p. 1., viewed 27 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article176996942.

[8] 1881 ‘Advertising’, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.:1848 – 1957), 8 December, p. 5., viewed 27 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article11526074.

[9] 1878 ‘The Australasian Class Company.’, Leader (Melbourne, Vic.:1862 – 1918, 1935), 6 April, p. 20., viewed 16 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197280804.

[10] 1878 ‘Advertising’, The Record and Emerald Hill and Sandridge Advertiser (Vic.: 1872 – 1881), 27 December, p. 2., viewed 16 Jul 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article108500877.

[11] 1884 ‘Insolvency Court.’, The Age (Melbourne, Vic.:1854 – 1954), 18 November, p. 6., viewed 16 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article191474998.

[12] 1895 ‘A Big Insolvency.’, The Age (Melbourne, Vic.: 1854 – 1954), 20 November, p. 5., viewed 18 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197195717.

[13] 1888 ‘Items of News.’, Standard (Port Melbourne, Vic.:1884 – 1914), 13 October, p. 2., viewed 20 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article164932918 and 1888 ‘Current Items.’, Balmain Observer and Western Suburbs Advertiser (NSW: 1884 – 1907), 6 October, p. 4., viewed 18 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article132302693.

[14] 1889 ‘New Insolvents.’, The Age (Melbourne, Vic.: 1854 – 1954), 22 August, p. 5., viewed 18 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197323076.

[15] 1909 ‘Fatality at South Melbourne Gas Works’, Record (Emerald Hill, Vic.: 1881 – 1954), 20 March, p. 3., viewed 21 Mar 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article162596968.